‘Rebuilding Delfzijl’, de Groningse versterkingsopgave

Tussen 2018 en 2023 was ik als stedenbouwkundige bij de gemeente Eemsdelta werkzaam in de ingrijpende herstel- en transformatieopgaven die noodzakelijk zijn door aardbevingsschade in Groningen. Als ruimtelijk strateeg en stedenbouwkundig ontwerper was ik betrokken was bij ontwerpopgaven voor vele honderden woningen, scholen en zorginstellingen in en rondom Delfzijl, Appingedam en Loppersum. Dit is een unieke opgave in Nederland. Om deze unieke opgave te delen met vakgenoten die werkzaam zijn in andere landen, heb ik voor de ‘ISOCARP Review of World Planning Practice, Volume 16: Post-Oil Urbanism’ het artikel ‘Rebuilding Delfzijl, Recovering from Earth Quakes Inducted by the Extraction of Natural Gas’ geschreven. Het boek met dit artikel is eind 2020 uitgebracht als onderdeel van het 56e ISOCARP World Planning Congres ‘Post-Oil City: Planning for Urban Green Deals’.

Introduction

The port city Delfzijl (25,000 inhabitants) is situated in Groningen (584,000 inhabitants), the north-eastern province of the Netherlands. Surrounding the city is the Groningen gas field, discovered in 1959. This is the largest natural gas field in Europe and the eight-largest in the world. Since 1986, rapid and extensive exploitation of this gas field has caused well over 1,400 small and damaging earthquakes in the region. Delfzijl is situated close to Loppersum, the epicentre of these continuing earthquakes. The effect of these earthquakes, described as a “disaster in slow motion”, sparked a fierce national political debate and has drawn international media coverage.

As a result of these earthquakes, nearly all public buildings (schools, libraries, healthcare institutions, and churches) and thousands of houses have been declared unsafe and need to be renovated or demolished and rebuild in the next few years. This massive rehabilitation project triggers both challenges and opportunities to improve the urban fabric and to transform the port city Delfzijl into a sustainable and more liveable city. This inevitable restructuring of the city and settlements in the neighbouring municipalities of Appingedam and Loppersum also requires a fundamental strategy on public participation and participatory urban planning and design.

This article describes the challenges of planning, design, and the rapid transformations of Delfzijl in the context of dynamic, demographic and economic uncertainties.

About Delfzijl

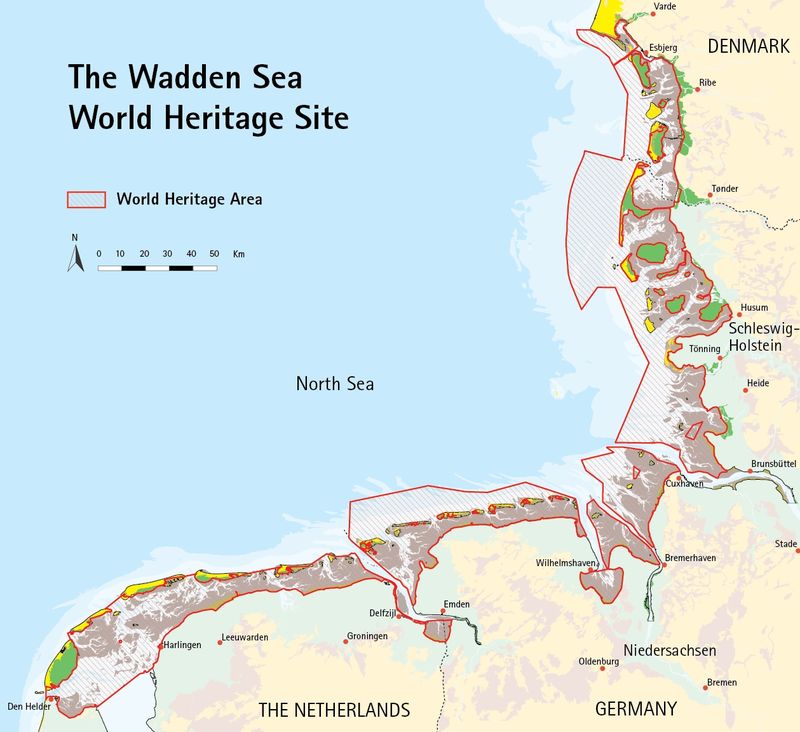

Delfzijl is a port and industrial city, surrounded by historic landscapes and villages, at the Eems Estuary now part of the Wadden Sea UNESCO World Heritage Site that extends over the northern coasts of The Netherlands and Germany and the western coast of Denmark. The settlement was created around 1300 AD when the first of several canals with sluices and sea locks were built as part of the regional water system and to improve the connections by ship between the city of Groningen and the sea. Due to its strategic position, Delfzijl was one of the fortified cities in defence of the northern coast of the Netherlands between 1580 and 1875. After the demolition of the fortifications and the construction of new waterways, railway lines and motorways, Delfzijl became the maritime centre of the northern part of the Netherlands, first with shipbuilding, brickworks and sawmills and later with cargo shipping, stevedoring, offshore, towage, transport and lifting.

After the discovery of salt and natural gas in the region in the 1950s, Delfzijl became an industrial port with a strong chemical cluster and an aluminium plant. Around 15% of all the chemical products that are produced in the Netherlands come from Delfzijl. The chemical cluster Delfzijl is a sustainably developed industrial area for chemical related companies, connected to each other like a chain. The industries, governments and knowledge institutes in the region work together towards a shared ambition: changing the nature of chemistry.

Since 2009, several large wind and solar parks are in operation to meet the increasing demand for green electricity. With the green energy mix provided by wind turbines, solar fields, biomass and hydropower (from Norway), and the opportunities offered by the agricultural hinterland, Delfzijl became a major bio-based location in North-West Europe. Waste is used increasingly as a raw material for the chemical sector or is turned into energy. The circular economy and bio-based industries now play an important role in Delfzijl, which is rapidly turning into the preferred location for mechanical and chemical recycling and waste industry.

The chemical industries, the enlargement of the sea locks, broadening the Eemskanaal, combined with the construction of outer and inner port basins, attracted more industries and more laborers which resulted in a rapid urban development of Delfzijl. In the 1950s and 1960s, as the economic prospects were grand and compelling, the Province of Groningen commissioned the development of a second industrial port to the north of Delfzijl, the Eemshaven. Also, Delfzijl and its neighbouring municipalities made preparations to build a series of new towns for more than 100,000 inhabitants between the two ports, starting with the development of Delfzijl North.

Delfzijl’s growth increased an average of 500 inhabitants every year, from 25,000 inhabitants in 1960 to almost 35,000 in 1980. After 1980, due to economic recession and the restructuring and automation in the industries, employment declined. Consequentially, the number of inhabitants dropped back to 25,000 in 2020. This residual population is expected to reach 20,000 inhabitants in 2030, due to aging and demographic decline.

This population decline has affected the demand and quality of the housing market. Between 1995 and 2010 several thousands of relatively newly built houses needed to be demolished. A second round of restructuring the housing stock in the near future cannot be ruled out. The changing population has also caused a negative impact on the spatial and social perception of Delfzijl. It now is a city with an abundance of infrastructure, partially derelict and underused industrial areas, a distorted urban fabric and many left-over areas where residential areas were developed, built and transformed into green spaces without a clear use or purpose.

However, Delfzijl hopes for a better future, especially after optimistic figures that the population fell by only fifty inhabitants in 2019, the smallest decrease since 2002. In his 2020 New Year’s speech mayor Gerard Beukema expressed his hopes for growth in the future sparked by the hundreds of houses that will be renovated or rebuild. But first the inhabitants have to bite the bullet. “All construction work will cause tensions and inconvenience. But those who want to be beautiful must suffer pain. We want Delfzijl to be recognized and valued again as a municipality where it is not only good work, but also good housing and accommodation”.

Rebuilding Delfzijl comes with additional challenges and opportunities. Delfzijl can take advantage of this huge restructuring by redefining its relation to the Eems, the Wadden Sea, the many water connections and its port as well as upgrading the overall resilience and attractiveness of the city. It is a multi-layered operation that includes the active involvement of its citizens, and the accelerated anticipating on climate adaptation and energy transition, which is needed more than ever now the extraction of natural gas from the Groningen gas field inducted the damaging earthquakes.

The Groningen gas field

The Groningen gas field is operated by the Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij BV (NAM), a joint venture between Royal Dutch Shell and ExxonMobil with each company owning a 50% share. Natural gas at this field is extracted through drilling, a process which can cause earthquakes as the ground settles.

Since the start of the gas extraction, earthquakes exhibited an exponential growth with time. On 16 August 2012, the heaviest induced earthquake in the Netherlands, with a magnitude of 3.6, occurred with its epicentre only a few hundreds of metres below the surface of Huizinge, 20 kilometres from Delfzijl. While seemingly moderate in magnitude, the sheer number of hundreds continuous earthquakes act as a physical stressor to living conditions and give an adverse outlook to the long-term structural integrity of homes and buildings.

The continuous sequence of small earthquakes has affected thousands of houses and nearly all public buildings (schools, libraries, healthcare institutions, churches, sporting facilities) in the Eemsdelta region. Technical assessments indicate that these houses and public buildings need to be renovated or demolished and rebuild in the next few years as they are unsafe. The damages and collateral effects of the earthquakes inducted by the extraction of natural gas are monitored and assessed by the National Coordinator for Groningen. This is a collaboration of the Groningen municipalities in the earthquake zone, the Province of Groningen and the Central Government. The task of the National Coordinator for Groningen is not only to reactively repair the damages, proactively reinforce homes and other buildings, but also to enhance the quality of life and sustainability and to reinforce the regional economy.

After protests in Groningen, the Dutch government decided in 2014 to cut output from the gas field and pay those affected by the earthquakes a compensation worth 1.2 billion Euros, spread over a period of 5 years. In 2018 the government announced it would shut down the gas extraction entirely by 2030 to limit seismic risks and for safety reasons. Recently (2019) The Dutch government announced a further acceleration of the decommissioning of the field, stopping all regular extraction of natural gas by 2022, eight years earlier than initially planned. Consequentially, two hundred of the Netherlands’ biggest companies have been requested by their government to stop sourcing fuel from the Dutch gas fields within four years following a series of increasingly significant earthquakes.

Ending the extraction of natural gas by 2022 is a very hard decision as the Groningen gas field is regarded as one of the corner stones in the energy supply of north western Europe. On the other hand, this development is a significant accelerator and game changer in the necessary transition of the energy production and energy infrastructure in the Netherlands, with opportunities for economic development and the sustainable transformation of the built environment. According to the 2019 National Climate Agreement seven million homes and one million buildings, many of which are moderately well insulated and virtually all of which are heated by natural gas, will be insulated, use renewable heating and will use and generate clean electricity by 2050. This process will be carried out incrementally and will involve cooperation of residents and owners of these buildings.

Challenging changes in the Netherlands

Meanwhile, the Netherlands Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, all twelve provinces, 21 regional water authorities, and 355 municipalities in the Netherlands are preparing to implement the new Environmental Planning Act (Omgevingswet). This Act seeks to modernize, harmonize and simplify current rules on land use planning, environmental protection, nature conservation, construction of buildings, protection of cultural heritage, water management, urban and rural redevelopment, development of major public and private works and mining and earth removal. It proposes to integrate all these rules into one legal framework.

It is expected that the Environmental Planning Act will enter into force and take effect in 2022. It shifts of responsibilities from ministerial authorities to provinces and regional water authorities, and from provinces to municipalities. All levels of government need to prepare for unprecedented changes in governance, responsibilities and operations.

Through this Act the government intends to combine and simplify the regulations for spatial projects. The aim is to make it easier to start up projects such as the construction of housing on former business parks, or the building of wind farms. Current environmental legislation consists of dozens of laws and hundreds of regulations for land use, residential areas, infrastructure, the environment, nature and water; each has their own starting points, procedures and requirements. This makes the present environmental and planning legislation too complex and time consuming for municipalities that have to work with it. The new Act will replace fifteen existing laws, including the Water Act, the Crisis and Recovery Act and the Spatial Planning Act. The provisions of eight other laws will be transferred to the Environmental Planning Act as well.

The (draft) National Strategy on Spatial Planning and the Environment (Nationale Omgevingsvisie – NOVI) is the spatial policy strategy based on the Environmental Planning Act. The National Strategy on Spatial Planning and the Environment replaces the National Policy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning (2011) and provides a sustainable perspective for both the built and the natural environment. It defines and sets a course to fulfil national interests through 2050. Those interests are clustered in four priorities: 1) Space for climate adaptation and energy transition, 2) Sustainable economic growth potential, 3) Strong and healthy cities and regions, and 4) Future-proof development of rural areas.

The intention is that the National Strategy on Spatial Planning and the Environment will be adaptable to new developments, in a permanent and cyclic process. The approach is a shared responsibility of the central, provincial and municipal governments working together as one body. The National Strategy on Spatial Planning and the Environment was drawn up in consultation with the responsible Ministries, provinces, water authorities and municipalities. Input was also sought from advisory boards, centres of knowledge, the private sector, civil society organizations and individual citizens. The dialogue with and between all these stakeholders will not cease when the (draft) NOVI is published. It will remain an open process of which public consultation represents an intrinsic part.

Delfzijl also is an active and strategic partner in defining the Groningen Regional Energy Strategy. Groningen is one of the 30 energy regions in the Netherlands that contribute to the National Program of Regional Energy Strategies. The National Program aims to implementation of the National Climate Agreement (2019), the Dutch elaboration of COP21, the international Paris Agreement on climate change, greenhouse gas mitigation, adaptation and finance (2015). All 30 energy regions are requested to significantly reduce CO2 emissions by 2030, to half the levels found in 1990. Another cooperative project is to investigate where and how best to generate sustainable electricity on land (wind and sun) and to determine which sources feasibly can be used to supply heat to neighbourhoods and buildings instead of using natural gas. In a Regional Energy Strategy, each energy region describes its own choices.

Delfzijl has much to offer to the Groningen Regional Energy Strategy as the city has developed itself as a major energy cluster. The chemical and waste industries produce enormous quantities of residual heat and multiple wind and solar parks are located in and around the port of Delfzijl. Future extensions of these wind and solar parks are now in preparation.

Planning for a Dynamic Eemsdelta

Delfzijl’s decline in population and the administrative reform of municipal governance in the Netherlands has led to the situation that, in 2021, the Municipality of Delfzijl will merge with two neighbouring municipalities, Appingedam (11,500 inhabitants) and Loppersum (9,500 inhabitants), that also are severely affected by earthquakes. The new municipality (46,000 inhabitants) will carry the name of Eemsdelta, referring to its location on the Eems Estuary, part of the Wadden Sea. This merger will make that the new municipality is better equipped to deal with the earthquake damages. It is expected that in few years well over 3,000 houses will be demolished and rebuilt.

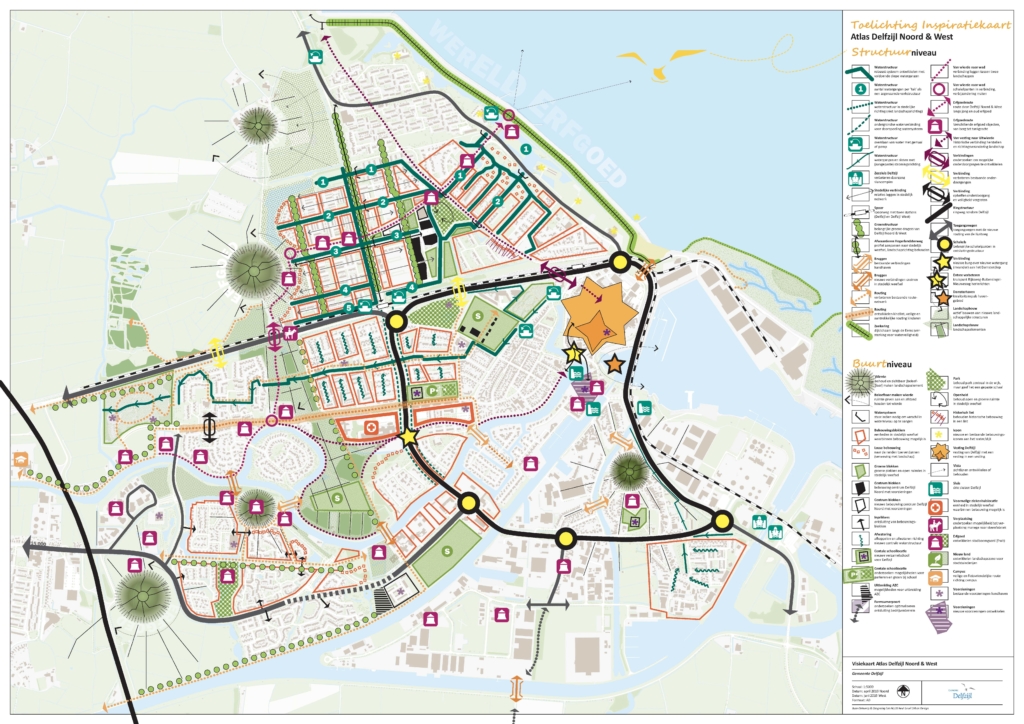

In the midst of this perfect storm of rapid changes and developments, the municipality had no other choice than to prepare and implement new policies, kick start urban renewal and residential redevelopments and communicate with its inhabitants about the necessary and compelling changes within a timespan of five to ten years. This inevitable restructuring of residential areas and public buildings in Eemsdelta requires a fundamental strategy on public participation and participatory urban planning and design. It also evokes challenges and opportunities to improve the urban fabric and to transform the port city Delfzijl into a more sustainable, attractive and compact city.

Delfzijl will be overhauled in the coming years. To start with, more than 600 new houses will be built at twenty plus locations. Schools, care facilities, the library and theatre will also be rebuilt. “Delfzijl soon will turn into a large construction site”, according to mayor Gerard Beukema. By far the largest project is the demolition and rebuilding of 527 houses in Delfzijl Noord. Due to the earthquakes, the houses do not meet the safety standards. Full renovation of these houses is not an issue as the calculated costs will surpass the current real estate value. All affected residents get the opportunity to rent or buy a new home at other locations in newly developed residential areas. The reinforcement operation of the renovation and rebuilding houses and public buildings does not stop there. According to Beukema, “The total program contains more than 5,000 houses in our municipality. That is more than 40 percent of our housing stock, which is a huge task for Delfzijl.”

In the neighbouring settlements Appingedam and Loppersum demolition and rebuilding houses in situ has proven to be troublesome as residents resent to move to temporary houses and move twice within 9-18 months. The municipality of Delfzijl, however, has chosen to build the 527 houses on the vacant and available plots first and subsequently demolish the damaged houses that are left behind. As these plots are available from previous redevelopments between 1995 and 2010, this can be done quite rapidly and efficiently without having to build temporary houses. The need for the rapid renewal of its cultural cluster with the centre of the arts, the library and theatre, however, forced the city to double its efforts and pace to redevelop, improve and intensify the core and fringes of its inner city.

The Eemsdelta area will receive 82 million euros from the National Coordinator for Groningen in compensation of the damages. An important goal is to stimulate employment, but that is, according to Beukema, insufficient. “Extra efforts are needed to guide people who live in this region to access the labour market. Increased efforts are also needed in the field of education, training and supervision. Starting in Delfzijl Noord, to give children from disadvantaged backgrounds a better future.”

The challenges and opportunities of rebuilding the port municipality are obvious. The requires a roadmap on public participation and mobilizing the inhabitants and communities to improve and upgrade the quality of life and to transform Delfzijl into an attractive, safe, sustainable and healthy city. Building back a better Delfzijl offers an additional impulse in making the historic city centre of Delfzijl more compact and renewing the functional relation and spatial experience with the waterfront on the Eems Estuary and the Wadden Sea UNESCO World Heritage Site through placemaking.

With so many projects and developments, the tailwind of urgency, ample budgets and additional and specialized staff, the inhabitants can be easily forgotten. But in Delfzijl the inhabitants are well informed, represented and activated. Delfzijl prepared and hosted numerous town hall meetings, dedicated workshops with many actors and stakeholders, discussion evenings, and participatory design sessions and will continue to do so. In November 2019, the Municipality of Delfzijl hosted the first of a series of expositions and housing markets for its citizens. The purpose of these two-day events is to enable local housing association and developers to proactively inform and to receive feedback from potential tenants and home buyers about the new developments and to bring supply and demand together. The first event in November 2019 attracted over 2,000 visitors. For the second event in June 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, all information was shared and exchanged through a dedicated website, social media and with billboards on the twenty plus locations.

The Environment and Planning Act requires and challenges provinces and municipalities to draft their own regional and local strategies on spatial and environmental planning. In preparation, the municipality reassessed its almost lost and forgotten characteristics and qualities of its cultural heritage of landscapes and villages. This has been documented in a manual, a living document that will updated on a regular basis. The Municipality of Delfzijl also prepared an ‘Opening Statement’ for the Delfzijl Strategy on Spatial and Environmental Planning that describes five ambitions: 1) Innovative demographic transition, 2) Leading the way in energy transition, 3) Making space for water, 4) Balancing between economy and residents, and 5) Improve accessibility and connectivity of Delfzijl. The Opening Statement outlines Delfzijl in 2020, indicates the tasks for 2030 and offers a future perspective to 2040. In addition, it examines the main outlines and the spatial consequences of the tasks and themes for the inner city, the port and the northern and southern landscapes and villages of the municipality.

Towards a ‘silent’ Green Deal for Eemsdelta

The unprecedented challenges that face Delfzijl provide unexpected and unavoidable opportunities to build back a better and more resilient municipality with energy efficient and climate adaptive residential areas. One of the core conditions for the redevelopment is that all new residential areas will become energy neutral, have solar panels, and are resistant to new earthquakes. In the less dense portions of the municipality, all upcoming interventions and redevelopments accelerate the need to upgrade outdated infrastructure and to improve crucial and safe networks for cycling, water storage, landscape and ecology that will make a better and more attractive city. The Opening Statement of the local Strategy on Spatial and Environmental Planning refers to the five core values of Eemsdelta.

- Attractive: Eemsdelta becomes an attractive area for current and future residents, companies, recreationists and tourists, focusing on the heritage of its canals, water system, landscapes and settlements, and shaping liveable places in the aftermath of the earthquakes;

- Reliable: Eemsdelta provides insight into future developments in the municipality, thereby creating a reliable and clear picture for the inhabitants safeguarding the urban resilience, ecological capacity and climate change adaptation;

- Connected: Eemsdelta becomes an accessible area for its citizens, visitors, businesses and cargo, enhancing rural and urban connectivity by sea, water, road, rail, and the internet to create a vital environment for economic development;

- Innovative: Eemsdelta ensures its economic diversity and resilience to utilize its strategic positions in the Groningen Regional Energy Strategy and in the bio-based and circular economy;

- Community: Eemsdelta improves the quality of life and creates a healthy and an inclusive urban environment for and with its residents, social organizations and local businesses.

These core values form the compass or dashboard of the ‘silent’ Green Deal for Eemsdelta. Silent, as this is not widely communicated as a ‘green deal’. For Eemsdelta, as building back a better Delfzijl will take five of more years and will be part of the policies and operations of the merged and newly formed municipality in 2021 and beyond. The process to rapidly transform the port city Delfzijl, and subsequently Eemsdelta, into a more sustainable, attractive and liveable city and a more resilient and equitable society is inevitable dynamic and will evoke many challenges and opportunities. It requires both a grand and bolt vision on values, spatial development and placemaking, as well as a permanent attitude of reflection and evaluation.

Download hier de PDF van dit artikel: Artikel Rebuilding Delfzijl